The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America recently published a statistical report concerning people’s perceptions of their choices to be more energy efficient. The report was written by Shahzeen Z. Attaria, Michael L. DeKayb, Cliff I. Davidson, and Wändi Bruine de Bruinc, who brought their own skills as statisticians, social scientists, and engineers to the project. Indeed, the reading the details of the report requires some understanding of statistics and means graphs. But the narrative makes clear that people perceive themselves as being far more energy efficient than they in fact are.

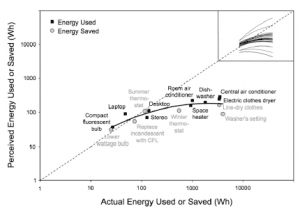

Graph of Some Household Objects & Their Energy Use

The effort of the surveys was to focus on what people perceive as especially energy-efficient in terms of appliances or actions (like turning off a light when leaving a room). The efforts of those surveyed were divided into Energy Curtailment or Energy Efficiency. One of the findings is that most people pride themselves on energy curtailment (not in itself a bad thing, of course), when savings are quite minimal in contrast to investing in energy efficiency, like purchasing EnergyStar appliances or insulating an attic. “For example, participants estimated that line-drying clothes saves more energy than changing the washer’s settings (the reverse is true) and estimated that a central air conditioner uses only 1.3 times the energy of a room air conditioner (in fact, it uses about 3.5 times as much).” Overall, “Participants were poorly attuned to large energy differences across devices and activities and unaware of differences for some large-scale economic activities (transporting goods by train vs. truck) and everyday items (aluminum vs. glass beverage containers). Knowing these relative magnitudes would allow individuals to make more informed choices regarding energy-saving behaviors.” For example, respondents understood that trains are more energy efficient than trucks for shipping goods, but they greatly underestimated how much more efficient.

The reasons suggested include the fact that the media do not tend to report details of differences (only that some activities or goods are more or less efficient), or that those in energy-efficient industries (like trains, which are 10 times more efficient than trucks) do not market themselves with sufficient information for the general public. Unfortunately, customers must take responsibility as well. Energy curtailment does not offer much of an improvement, but it usually requires only moment-by-moment decisions. Energy efficiency requires some planning and investment up front before the savings (though much bigger) start rolling in.

Relative to experts’ recommendations, participants were overly focused on curtailment rather than efficiency, possibly because efficiency improvements almost always involve research, effort, and out-of-pocket costs (e.g., buying a new energy-efficient appliance), whereas curtailment may be easier to imagine and incorporate into one’s daily behaviors without any upfront costs.

The need for hard facts on energy efficiency, and the costs to strive for it, can be part of a drive to reinvigorate the economy. The question might be whether traditional industries try to block such developments or simply miss the opportunity, as General Electric has done by not converting its US plants to make Compact Florescent Lamps.