Earlier this summer The Monitor Institute released a significant white paper penned by Katherine Fulton, Gabriel Kasper, and Barbara Kibbe that wants to challenge philanthropic organizations to see beyond the present fundraising doldrums toward the structural changes that requires such organizations to behave differently, whatever the economic environment. Their answers challenge some of the standard presuppositions they believe that nonprofit and fundraising organizations have been using since the turn of the twentieth century.

One of the qualities that makes this particular study especially worth reading in its entirety, is that the group started their research in the relatively booming year of 2000, and continued to collect information through 2009. The authors thus have collected materials through a moderate recession, a relative upturn (or bubble), and a stunning collapse. When they distinguish between economic variables and fundamental changes in fundraising, they have a rich variety of situations to draw upon. For the authors, this past decade has been about ensuring internal/intra-organizational efficiency to make the most of the dollars that could be raised. The future, though, will be about reaching out to other organizations and being ready to adjust within that network to deal with the issues that the networked groups need to tackle.

Whereas the cutting edge of philanthropic innovation over the last decade was mostly about improving organizational effectiveness, efficiency, and responsiveness, we believe that the work of the next ten years will have to build on those efforts to include an additional focus on coordination and adaptation:

COORDINATION—because given the scale and social complexity of the challenges they face, funders will increasingly look to other actors, both in philanthropy and across sectors, to activate sufficient resources to make sustainable progress on issues of shared concern. No private funder alone, not even Bill Gates, has the resources and reach required to move the needle on our most pressing and intractable problems.

ADAPTATION—because given the pace of change today, funders will need to get smarter more quickly, incorporating the best available data and knowledge about what is working and regularly adjusting what they do to add value amidst the dynamic circumstances we all face.

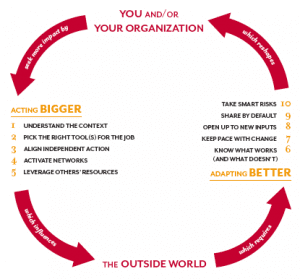

Fulton’s, Kasper’s, and Kibbe’s leitmotif concerns the need to ‘Act Bigger and Adapt Faster,’ and as their infographic suggests (from p.7), the buildup of success comes from an interactive relationship both among similar organizations and between organizations and their donors or recipients. All such exchanges need analysis and adjustment, not unlike the ways for-profit businesses try to be as sensitive as possible to changes in the marketplace. Each of the five points on the left and right ‘sides’ of the cycle gets enumerated in the report, and the authors present a number of case studies that show successful implementation of the points in question. For our purposes, we stick with the larger theme of the two new skill sets.

‘Acting Bigger’ means not just developing networks but using them to align resources (human, time, and capital) across the networks to solve the issue at hand. Sociologically speaking, even the most ‘progressive’ organizations tend toward an institutional inertia that must constantly be challenged. Networking resources and information means that if one organization’s staff is having a quiet time and not being as productive or proactive as it can be, others in the network might disturb that particular group and inspire (or goad) it into action by sharing news from the outside and/or from what has inspired them.

Of course, with all groups in the network humming along to their rhythms and strengths, the opportunities for change outside the philanthropic group improve exponentially. Thus each group sees its own efforts multiplied through the coordinated effect of others in the network. The process can be a bit slower than a single organization tackling a single problem, but the results are more impressive and more long-lasting, argue the authors. And they have the case studies to back up the point.

As for ‘Adapting Better,’ the authors take on a ‘good-cop-bad-cop’ tone as they discuss how easy it is for well meaning philanthropy to become an autonomous, linear, social – and stagnant – activity, rather than a game-changing enterprise:

It’s high time to trade in the false comfort and overprecision of evaluating individual programs and projects against linear logic models for a context-based approach to cultivating better and better judgment over time for multiple actors in complex systems. Effective measurement in the future will evolve in ways that parallel the new paradigm for philanthropy more broadly: it will be fully contextualized, aggressively collective, real-time, transparent, meaningful to multiple audiences, and technologically enabled. (p.22)

Social media and aggregation of data play important roles in the second half of the report, by the main issue the authors tackle can perhaps be described by Chapter 9: “Share By Default.” “By increasing the amount of information that is available, funders can create an environment where stakeholders can find what they need to make smarter decisions, grounded in the experience and knowledge of others. For mission-driven organizations like foundations, it makes sense to start from a place of sharing everything and then make a few exceptions rather than a place of sharing little where transparency is the exception.” (p.28) The issue is not the medium of sharing, but that that sharing is the expectation (again, internally and externally), with an appreciation of the need, occasionally, to ensure privacy and/or safety.

The authors are well aware of the tendencies toward inertia that can make their program difficult to implement. They also are quick to point out that though they believe they have described important mileposts toward a new philanthropy, they realize that different organizations will achieve these goals in different orders of priority and ease.

The challenge and the opportunity for the next decade is to make it easier for individuals and independent institutions to choose what is best for the collective whole without setting aside their own goals and interests. We believe this can happen through a combination of: new data and tools, enabled by new technology; new incentives, provided by changes from outside philanthropy; and new leadership, sophisticated about what it takes to succeed in a networked world.

Though it is a more substantive read than many of the links we have provided over the months on our blog, we believe the time investment is well worth it. The Monitor Institute‘s study is a deep look at successful organizations, their networks, their tools, and their outcomes. The analysis will challenge us all to reconsider how we do what we do.