As we have often discussed on this blog, charity giving has taken a notable downturn with the economy over the last couple of years. Nevertheless, that downturn has not been as steep as the economy itself, suggesting people’s ongoing commitments to help others and try to have a greater influence with their money than boosting Cyber Monday figures. But despite the downturn, some institutions – especially universities and research centers as well as cultural/art houses – can still call in single donations of over $1 million dollars. Mark Phillips, the founder and CEO of Bluefrog (in the United Kingdom) asked how those particular institutions have managed to continue to get such big donations. His answers have more to do with the treatment of the prospective donor than with the wealth of that donor.

Mark’s analysis is based on the Coutts Million Pound Donors Report 2010, recently published in Britain. It states that the numbers of donors giving at least ₤1 million have slipped in the last year, but the overall amount has remained fairly steady. He also points to the striking distribution of those high-pound donations:

[Much of the money goes into trusts and investments,] with 58% [of the outright donations] going to higher education and 13% going to arts and culture. ‘Traditional’ charities didn’t do too well. International aid received 5%, human services and welfare generated 4% and environment and animals brought in just 1% of the top-end gifts.

Americans do not trade in pounds, and perhaps a single $1 million donation to your organization seems pretty far fetched at the moment. But the tactics and the relations Mr. Phillips presents are translatable and scalable.

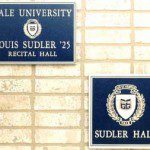

One of the things universities and opera houses are especially good at is conferring status on the donor, be it a plaque in the library, a wine reception with the soprano lead, or a prime parking space near the school’s football stadium. Another one is that these institutions can use their long-standing traditions of communication and openness to give meaningful access to the donor, whether it is to a planning-committee meeting or a long-term strategy round table, or even to register for some classes for free.

One of the things universities and opera houses are especially good at is conferring status on the donor, be it a plaque in the library, a wine reception with the soprano lead, or a prime parking space near the school’s football stadium. Another one is that these institutions can use their long-standing traditions of communication and openness to give meaningful access to the donor, whether it is to a planning-committee meeting or a long-term strategy round table, or even to register for some classes for free.

A third, and we think vital, skill these institutions have developed is the acceptance of long-term relationships that build enough trust to ask for mega-donations. Colleges have been around for decades, if not centuries. Art institutions for at least a century. Throughout that time, they have catered to and been supported by extremely wealthy individuals (most of the Colleges at Oxford were named after or by the first aristocratic ‘donor’ who funded it). These institutions have it in their DNA to court the interested wealthy, and to ask for major sums of money when the time is appropriate.

Again, your organization might not fit any of these particular categories. But does it have a plan to ask for some big donations from wealthy people interested in your work? Do you have an enticing set of options to offer in return? Can you show a tradition, even for a few years, of putting good money to good use?

The opportunities might be fewer, but they are there. Which is why you must be prepared to build them up and carry them through to everyone’s benefit.